|

|

- Search

AbstractThyroglossal duct carcinoma is uncommon, occurring in approximately 1% of all thyroglossal duct remnants. This rare neoplasm is characterized by relatively nonaggressive behavior with infrequent lymph nodal spread. Another rare neoplasm of the head and neck region is a carotid body tumor. A 78-year-old woman with a 3-year history of midline and bilateral neck masses was referred to us. Fine needle aspiration biopsies and a computed tomography scan suggested the diagnosis of thyroglossal duct carcinoma with cervical lymph node metastasis. Interestingly, the left-side neck mass was found to be splaying the carotid bifurcation, on computed tomography imaging. Carotid arteriography demonstrated a highly vascular mass in the bifurcation of the carotid artery that was compressing the internal and external carotid arteries. To our knowledge, this is the first reported instance of a thyroglossal duct carcinoma with neck metastasis accompanied by a carotid body tumor. In addition, the carotid body tumor in this case mimicked neck metastasis from the thyroglossal duct carcinoma.

Thyroglossal duct remnants represent a common developmental abnormality of the thyroid gland, and thyroglossal duct carcinoma (TGDC) reportedly occurs in approximately 1% of all thyroglossal duct remnants [1,2]. The incidence of lymph node metastases in papillary carcinoma of TGDC is rare (7% to 15%), compared with the incidence in primary papillary thyroid carcinoma [3].

Carotid body tumors (CBTs) are rare, benign neoplasms that originate from the neuroectodermal paraganglion. Originating from the afferent ganglion of the glossopharyngeal nerve, carotid body tumors are generally located at the carotid bifurcation [4]. Physiological activity is rare in these neoplasms, and these tumors generally exhibit a slow rate of growth, most often presenting asymptomatically as a space-occupying mass lesion noted clinically or radiographically [4,5]. To our knowledge, TGDC with neck metastasis accompanied by a CBT has not been reported previously. In addition, the CBT in the present case mimicked neck metastasis from the TGDC. We present a case of the CBT mimicking neck metastasis from the TGDC with a review of literature.

A 78-year-old woman visited our clinic, presenting with a 3-year history of a midline neck mass in the region of the hyoid bone and bilateral cervical asymptomatic neck masses. There were no constitutional symptoms, including fever, night sweating, fatigue, dysphagia, dyspnea, and weight loss. She reported that the mass was progressively increasing in size. The rest of the history was unremarkable. Physical examination showed a 3×3-cm rubbery, non-tender, semi-fixed midline mass and several enlarged lymph nodes at level II and III bilaterally. There were no pulsations or bruits on auscultation of the lateral neck masses. The results of routine laboratory tests, including blood chemistry, complete blood cell count, coagulation study, serologic testing, and urine analysis, were unremarkable. Electrocardiogram and chest X-ray were within normal limits.

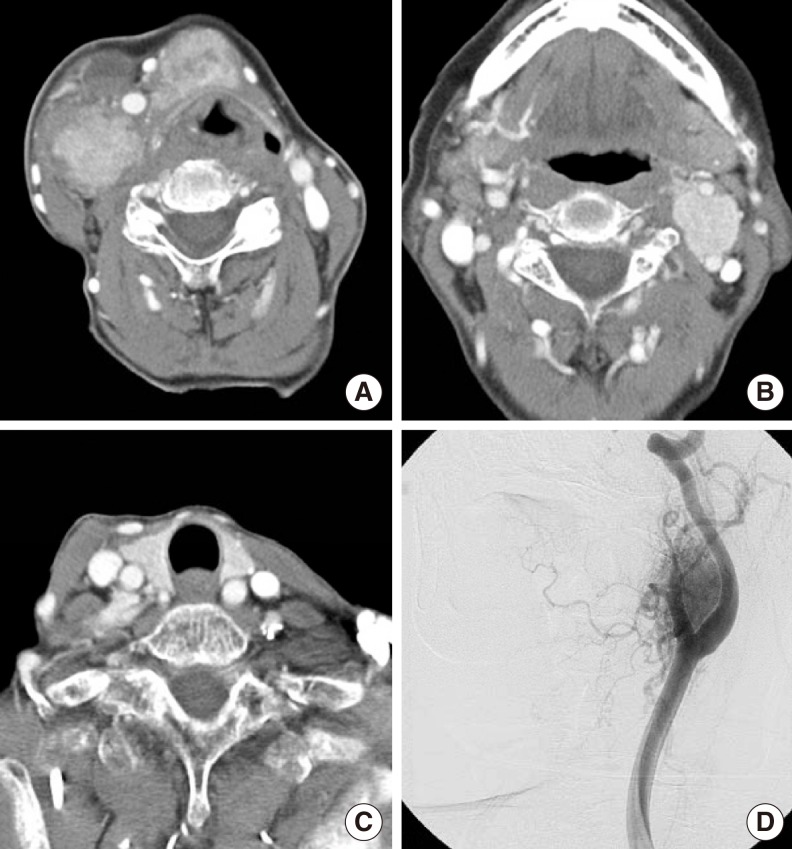

Computed tomography (CT) with contrast showed an irregularly marginated, round, heterogeneously enhancing mass at the level of the hyoid bone and multiple enlarged lymph nodes bilaterally at level II to III (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, the left-side neck mass was located at the carotid bifurcation, splaying the carotid bifurcation on a CT scan (Fig. 1B). However, the CT scan did not indicate other instances of abnormal lymphadenopathy in the left neck. Furthermore, neck CT and sonography did not demonstrate any mass involving the thyroid (Fig. 1C). Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was done on the midline mass and right-side neck mass. The results of FNAB suggested the possibility of papillary carcinoma and lymph node metastasis from papillary carcinoma, respectively. From the above results, we made the tentative diagnosis of TGDC carcinoma with bilateral neck metastasis. We planned to resect the masses, including bilateral neck dissection, in accordance with TGDC with neck metastasis. Splaying of the carotid bifurcation, however, is usually indicative of a CBT. Through the head and neck tumor board, we decided that carotid arteriography should be preoperatively performed to differentiate a CBT from lymph node metastasis. The mass was confirmed as a highly vascular mass in the bifurcation of the carotid artery that was compressing the internal and external carotid arteries (Fig. 1D). Ascending pharyngeal artery represented the major blood supply for this tumor. Our patient did not undergo carotid occlusion testing and embolization because of the potential complications. Results of screening for metanephrine and vanillymandelic acid in 24-hour urine samples were negative.

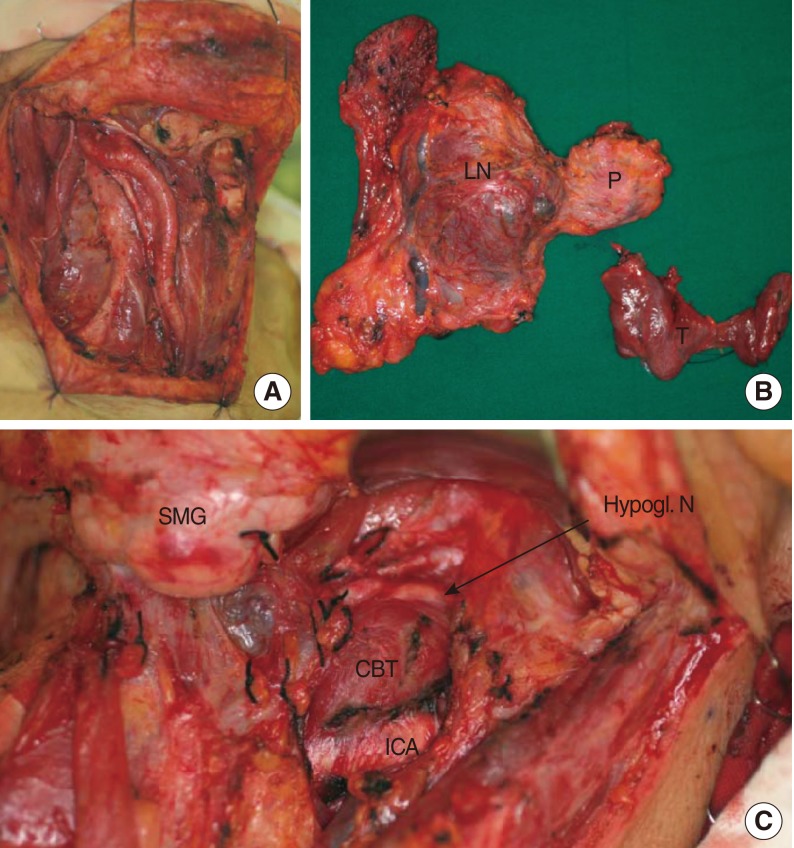

Subsequently, the patient underwent wide excision of the midline neck mass, including resection of the hyoid bone, total thyroidectomy, central neck dissection and right-side selective neck dissection (levels II-V), involving resection of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, spinal accessory nerve, and internal jugular vein. Although there was mild adhesion between the midline mass and surrounding soft tissue, we obtained a generous resection margin (Fig. 2A, B). During the exploration of left-side neck, we confirmed the CBT between external and internal carotid artery (Fig. 2C). We did not try to remove the left-side neck mass (CBT) because it had a tendency to bleed when touched and the patient was elderly.

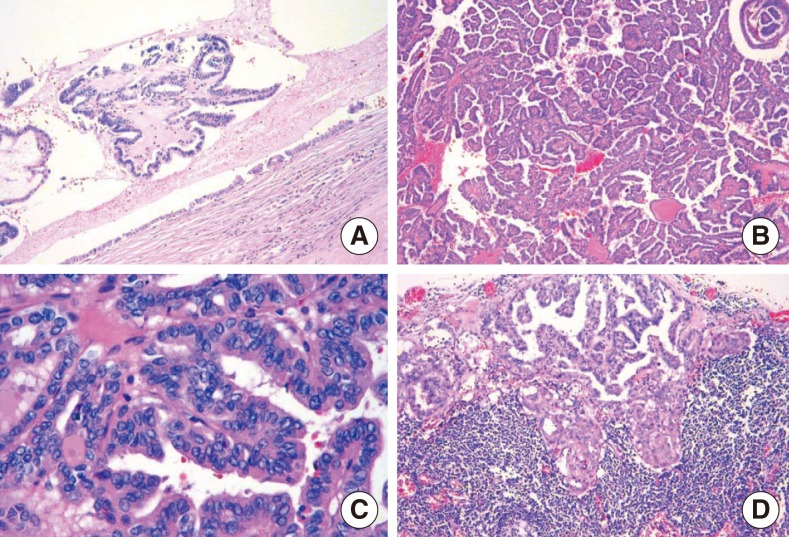

Histological analysis revealed that a thyroglossal duct cyst was lined by a single row of columnar epithelium and the tumor was composed of small and large papillary structures with fibrovascular cores (Fig. 3A, B). In addition, the tumor cells lining the papillary structures of the midline mass and cervical lymph nodes showed nuclear grooves and nuclear clearing, which are characteristic nuclear features of papillary carcinoma (Fig. 3C, D). The final histopathologic diagnosis was consistent with TGDC papillary carcinoma with perithyroidal soft tissue extension and subsequent multiple lymph node metastasis (17 out of 55 lymph nodes). However, we could not demonstrate any evidence of papillary carcinoma in the thyroid gland.

The patient refused adjuvant therapy with 131I after surgery and was only treated with levothyroxine supplementation. At the 2-year follow-up, the patient remained free of disease.

Although a thyroglossal duct remnant is the most common congenital midline neck mass, TGDC is thought to be extremely rare, occurring in approximately 1% of all diagnosed thyroglossal duct remnants [1,2].

CBT is a rare paraganglioma located near the bifurcation of the common carotid artery. The most common presentation is the development of an asymptomatic lateral neck mass without a thrill or bruit. Cranial nerve deficits are uncommon but may be seen in patients with masses greater than 5 cm in diameter [4, 5]. In the present case, the patient had no specific symptom except multiple neck masses.

On the rare occasion when TGDC is suspected clinically, preoperative physical examination, sonography, CT, MRI, and FNA may be helpful [6]. On physical examination, a neck mass that moves with swallowing and tongue movement is characteristic. The most common CT findings of TGDC are a solid nodule in the cyst, followed by calcification, an irregular margin, and a thick wall [7,8]. These findings, except calcification, corresponded to those in the present case. Furthermore, the CT scan in the present case demonstrated multiple conglomerated lymphadenopathies, suggestive of malignancy, and FNAB of the midline and right-side neck masses indicated the possibility of papillary carcinoma.

In CBT, either contrast-enhanced CT or MRI will clearly demonstrate a paraganglioma expanding the carotid bifurcation. The diagnosis of CBT is generally confirmed by carotid arteriography that shows a highly vascular tumor enlarging the space between the internal and external carotid arteries [5]. However, it was easier to overlook the possibility of a CBT in the present case for the preoccupation of neck metastasis from TGDC. Considering the splaying of the carotid bifurcation revealed by the CT scan, we fortunately suspected the possibility of left-side CBT. Carotid arteriography was performed to differentiate between CBT and lymph node metastasis.

Widstrom et al. [9] described three definitive criteria for distinguishing between primary TGDC and metastatic disease from a primary lesion inside the thyroid gland. First, the carcinoma should be in the wall of the thyroglossal duct cyst. Second, the TGDC must be differentiated from a cystic lymph node metastasis by histological demonstration of a squamous or columnar epithelial lining and normal thyroid follicles in the wall of the thyroglossal duct cyst. Third, malignancy should not be present in the thyroid gland or any other possible primary site. These criteria corresponded to the pathologic findings in the present case.

The nonfamilial association of carotid body tumors and papillary carcinomas of the thyroid was first described in 1968 [10]. It is unclear that whether there is a common pathogenesis for carotid body tumors and differentiated thyroid carcinomas, but Larraza-Hernandez et al. [11] and Kuratomi et al. [12] reported differentiated thyroid carcinomas associated with carotid body tumors. Because TGDC accompanied by a CBT has not been reported previously, it is necessary to search for TGDC as well as carotid body tumors in order to learn more about this association.

The most frequently used surgical therapeutic approach for TGDC is the Sistrunk procedure, which includes en-bloc resection of the thyroglossal duct cyst along with the tract, the middle part of the hyoid bone, and the soft tissues along the course of the thyroglossal duct to the level of the foramen cecum. The incidence of cervical lymph node metastasis from TGDC has been reported to be 7 to 15% [3]. When cervical lymph node metastasis is present, a reasonable approach is to perform a Sistrunk procedure, a total thyroidectomy, and selective neck dissection at an appropriate level [13].

CBTs are best treated by subadventitial resection. The most common complications of surgical resection are stroke and cranial nerve injury. Accordingly, for asymptomatic elderly patients, the indolent nature of CBTs has led to the recommendation of surveillance [14]. In our case, the patient underwent wide excision of the midline neck mass, including resection of the hyoid bone, total thyroidectomy, central neck dissection and selective neck dissection (levels II-V). However, we left the CBT unresected because we surmised that this CBT would not influence the life expectancy of this patient.

In TGDC, additional therapy is indicated if there is involvement of the thyroid gland, soft tissue invasion, or lymph node metastases. Ablation-dose radioactive iodine should follow, with subsequent scanning to exclude further tumor foci, as is standard practice for the majority of well-differentiated thyroid carcinomas [15]. The prognosis of TGDC is generally excellent, given adequate treatment.

Few reports about TGDC or CBT are present in the literature, and this is the first reported case involving the coexistence of TGDC with neck metastasis and CBT. Moreover, the CBT in the present case mimicked neck metastasis from the TGDC. If we had missed the possibility of CBT in the left-side neck mass, we would likely have encountered unexpected bleeding from the tumor and adhesion between the tumor and carotid artery during the left-side neck dissection. The present case demonstrates the importance of performing a careful physical examination and thorough evaluation of preoperative imaging studies before initiating surgical treatment of various head and neck tumors.

References1. Boswell WC, Zoller M, Williams JS, Lord SA, Check W. Thyroglossal duct carcinoma. Am Surg. 1994 9;60(9):650-655. PMID: 8060034.

2. Weiss SD, Orlich CC. Primary papillary carcinoma of a thyroglossal duct cyst: report of a case and literature review. Br J Surg. 1991 1;78(1):87-89. PMID: 1998873.

3. Plaza CP, Lopez ME, Carrasco CE, Meseguer LM, Perucho Ade L. Management of well-differentiated thyroglossal remnant thyroid carcinoma: time to close the debate? Report of five new cases and proposal of a definitive algorithm for treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006 5;13(5):745-752. PMID: 16538412.

4. Lack EE, Cubilla AL, Woodruff JM, Farr HW. Paragangliomas of the head and neck region: a clinical study of 69 patients. Cancer. 1977 2;39(2):397-409. PMID: 837327.

5. Netterville JL, Reilly KM, Robertson D, Reiber ME, Armstrong WB, Childs P. Carotid body tumors: a review of 30 patients with 46 tumors. Laryngoscope. 1995 2;105(2):115-126. PMID: 8544589.

6. Miccoli P, Minuto MN, Galleri D, Puccini M, Berti P. Extent of surgery in thyroglossal duct carcinoma: reflections on a series of eighteen cases. Thyroid. 2004 2;14(2):121-123. PMID: 15068626.

7. Branstetter BF, Weissman JL, Kennedy TL, Whitaker M. The CT appearance of thyroglossal duct carcinoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000 9;21(8):1547-1550. PMID: 11003294.

8. Samara C, Bechrakis I, Kavadias S, Papadopoulos A, Maniatis V, Strigaris K. Thyroglossal duct cyst carcinoma: case report and review of the literature, with emphasis on CT findings. Neuroradiology. 2001 8;43(8):647-649. PMID: 11548172.

9. Widstrom A, Magnusson P, Hallberg O, Hellqvist H, Riiber H. Adenocarcinoma originating in the thyroglossal duct. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1976;Mar-Apr;85(2 pt 1):286-290. PMID: 1267333.

10. Albores-Saavedra J, Duran ME. Association of thyroid carcinoma and chemodectoma. Am J Surg. 1968 12;116(6):887-890. PMID: 4302028.

11. Larraza-Hernandez O, Albores-Saavedra J, Benavides G, Krause LG, Perez-Merizaldi JC, Ginzo A. Multiple endocrine neoplasia: pituitary adenoma, multicentric papillary thyroid carcinoma, bilateral carotid body paraganglioma, parathyroid hyperplasia, gastric leiomyoma, and systemic amyloidosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1982 10;78(4):527-532. PMID: 7137085.

12. Kuratomi Y, Kumamoto Y, Sakai Y, Komiyama S. Carotid body tumor associated with differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1994;251(Suppl 1):S91-S94. PMID: 11894786.

13. Luna-Ortiz K, Hurtado-Lopez LM, Valderrama-Landaeta JL, Ruiz-Vega A. Thyroglossal duct cyst with papillary carcinoma: what must be done? Thyroid. 2004 5;14(5):363-366. PMID: 15186613.

14. Rush BF Jr. Current concepts in the treatment of carotid body tumors. Surgery. 1962 10;52:679-684. PMID: 14495345.

15. O'Connell M, Grixti M, Harmer C. Thyroglossal duct carcinoma: presentation and management, including eight cases reports. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1998;10(3):186-190. PMID: 9704182.

Fig. 1Axial view of a computed tomography scan with contrast showing a round heterogeneously enhanced mass with irregular margins at the level of the hyoid bone with multiple enhanced, enlarged cervical lymph nodes on the right, at level II (A). Note that a highly enhanced mass was located at the carotid bifurcation (B). There was no abnormal lesion in the thyroid gland (C). Carotid arteriography demonstrated a highly vascular mass at the bifurcation of the carotid artery that was compressing the internal and external carotid arteries (D).

Fig. 2Photograph of the intraoperative findings showing the surgical field of the right side of the neck after the completion of modified neck dissection (A). Surgical specimens showing the en bloc specimen of the neck dissection and thyroglossal duct carcinoma and total thyroidectomy specimen (B). Note that the CBT was located between the internal and external arteries, splaying the carotid bifurcation (C). P, primary tumor; LN, metastatic lymph nodes; T, thyroid gland; SMG, submandibular gland; CBT, carotid body tumor; ICA, internal carotid artery; Hypogl. N, hypoglossal nerve.

Fig. 3Histopathologic findings. A thyroglossal duct cyst lined by a single row of columnar epithelium (H&E, ×40) (A). The tumor was composed of small and large papillary structures with fibrovascular cores (H&E, ×100) (B). The tumor cells lining the papillary structures showed nuclear grooves and nuclear clearing, which are characteristic nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma. The nuclei showed a thick, irregular nuclear membrane, a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, and somewhat eccentric nucleoli (H&E, ×400) (C). A lymph node showing subcapsular sinusoidal metastatic carcinoma. The histological appearance of the metastatic carcinoma is the same as that of the primary tumor (H&E, ×100) (D).

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||